December 7, 2015: Yale University has launched a first-of-its-kind pilot program to put a price tag on the use of carbon — with some of the most prominent campus buildings playing a role in the experiment.

Twenty Yale buildings — including the Peabody Museum of Natural History, the School of Management’s Evans Hall, the School of Medicine’s Yale Physicians Building, and Yale Divinity School’s Sterling Divinity Quad — are taking part in the new carbon charge pilot program. So is Woodbridge Hall, the administrative home of Yale President Peter Salovey.

“The carbon charge concept originated as a proposal from Yale undergraduate and graduate students interested in using our campus as a living laboratory for applied research,” said Salovey, who announced the program with Provost Benjamin Polak. “Students were an integral part of the Presidential Carbon Charge Task Force, and many continue to serve in the pilot. Yale’s carbon charge pilot project is an exciting example of how students, faculty members, and staff can collaborate to build a more sustainable and innovative Yale.”

Placing a monetary value on carbon use is considered critical to creating an effective sustainability strategy and is a growing trend in the private sector. The idea is to prompt behavior changes at the individual and organizational levels by putting a price on the carbon dioxide used. Carbon dioxide is a byproduct of all activities that rely on the combustion of fossil fuels for power.

Yale has approximately 350 buildings and uses 3.6 million MMBtu of energy each year. The university generates 60% of its own power at its two co-generation power plants. The remaining electricity is purchased from United Illuminating Co., and natural gas is purchased from Southern Connecticut Gas to power the power plants. The university emits roughly 300,000 tons of carbon dioxide a year. In 2005, Yale pledged to reduce its primary greenhouse gas emissions 43% below 2005 levels by 2020. The university remains on track to meet this ambitious goal.

In 2014, Salovey outlined six sustainability initiatives for Yale, noting that, “Global climate change and its consequences are critical challenges for our time, and Yale has important and necessary roles to play in addressing them.” The initiatives included a $21 million capital investment in energy conservation and greenhouse gas reduction, an expansion of renewable energy, third-party verification of Yale’s greenhouse gas emissions, and the formation of the Presidential Carbon Charge Task Force.

The task force, chaired by Sterling Professor of Economics William Nordhaus, began looking into the feasibility of an internal carbon-pricing program in 2014. Earlier this year, the group presented its recommendations to Salovey. Among those recommendations were that Yale set a carbon charge at the social cost of carbon, currently estimated by the federal government to be $40 per ton of carbon dioxide.

“A key element is that the carbon charge program would expand Yale’s role as a pioneer in research, teaching, and designing practical applications of energy and climate policies,” Nordhaus said. “It would thereby contribute to society’s learning about ways to slow climate change while advancing Yale’s educational mission.”

One novel aspect of Yale’s pilot program is that it is essentially a quartet of experiments to find the best approach to carbon pricing. Each experiment will have five Yale buildings testing a particular manner of carbon pricing:

A market-based model will have Yale units competing with one another to earn rebates.

A target-based model will ask Yale units to meet specified carbon-use goals, in order to earn rebates that are applied to the unit’s annual budget.

An investment model will have Yale units paying a monthly carbon tax for the year. At the end of the year, units will get the money back, with a stipulation that a percentage of the returned money be spent on additional energy-saving measures within their building.

A price signal approach will present Yale units with detailed information about ongoing energy use, along with comparable information about past years’ energy use. The units also will receive regular updates on how their performance would translate into a straight carbon tax payment at the social cost of carbon, purely for informational purposes.

“This will help us arrive at the best model for Yale and allow us to share the lessons we learn with other institutions. That’s a key aspect of the program,” said Ryan Laemel, Yale’s carbon charge project coordinator. “There is no one-size-fits-all approach that works for internal carbon pricing.” (See "How Yale's Carbon Charge Project Works," below.)

The pilot program includes classrooms, residential colleges, laboratories, and offices. Other buildings taking part include Berkeley, Jonathan Edwards, and Pierson residential colleges; the Gilder Boat House; Kroon Hall; and the Yale Health Center.

“It goes beyond simply diversifying the size of the buildings or their carbon footprints. It includes a range of different activity types, budgeting categories, utilities used, building users, and equipment contained,” said carbon charge project manager Jennifer Milikowsky, who is a recent graduate of the joint degree program at the School of Forestry & Environmental Studies and the School of Management. “By doing this we’ll begin to learn how the success of the policies we are testing is influenced by these different characteristics and will help as we continue to expand and improve this project.”

In their announcement, Salovey and Polak noted that feedback from participants and an analysis of the program’s results would inform a broader campus conversation on the topic. “We believe that this pilot project can serve as a model for other institutions, expanding Yale’s role as a pioneer in researching, teaching, and designing climate change solutions,” they said.

Related Stories

Codes and Standards | Feb 21, 2022

More bad news on sea level rise for U.S. coastal areas

A new government report predicts sea levels in the U.S. of 10 to 12 inches higher by 2050, with some major cities on the East and Gulf coasts experiencing damaging floods even on sunny days.

Resiliency | Feb 15, 2022

Design strategies for resilient buildings

LEO A DALY's National Director of Engineering Kim Cowman takes a building-level look at resilient design.

Sponsored | Steel Buildings | Jan 25, 2022

Multifamily + Hospitality: Benefits of building in long-span composite floor systems

Long-span composite floor systems provide unique advantages in the construction of multi-family and hospitality facilities. This introductory course explains what composite deck is, how it works, what typical composite deck profiles look like and provides guidelines for using composite floor systems. This is a nano unit course.

Sponsored | Reconstruction & Renovation | Jan 25, 2022

Concrete buildings: Effective solutions for restorations and major repairs

Architectural concrete as we know it today was invented in the 19th century. It reached new heights in the U.S. after World War II when mid-century modernism was in vogue, following in the footsteps of a European aesthetic that expressed structure and permanent surfaces through this exposed material. Concrete was treated as a monolithic miracle, waterproof and structurally and visually versatile.

Sponsored | Resiliency | Jan 24, 2022

Norshield Products Fortify Critical NYC Infrastructure

New York City has two very large buildings dedicated to answering the 911 calls of its five boroughs. With more than 11 million emergency calls annually, it makes perfect sense. The second of these buildings, the Public Safety Answering Center II (PSAC II) is located on a nine-acre parcel of land in the Bronx. It’s an imposing 450,000 square-foot structure—a 240-foot-wide by 240-foot-tall cube. The gleaming aluminum cube risesthe equivalent of 24 stories from behind a grassy berm, projecting the unlikely impression that it might actually be floating. Like most visually striking structures, the building has drawn as much scorn as it has admiration.

Sponsored | Resiliency | Jan 24, 2022

Blast Hazard Mitigation: Building Openings for Greater Safety and Security

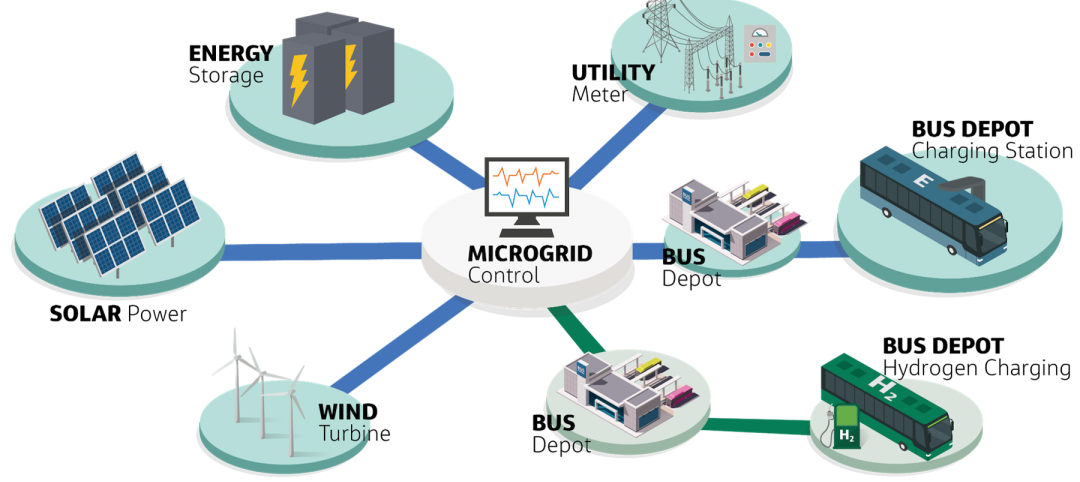

Microgrid | Jan 16, 2022

Resilience is what makes microgrids attractive as back-up energy controls

Jacobs is working with clients worldwide to ensure mission critical operations can withstand unexpected emergencies.

Sponsored | BD+C University Course | Jan 12, 2022

Total steel project performance

This instructor-led video course discusses actual project scenarios where collaborative steel joist and deck design have reduced total-project costs. In an era when incomplete structural drawings are a growing concern for our industry, the course reveals hidden costs and risks that can be avoided.

Resiliency | Oct 19, 2021

Achieving resiliency through integrated design

Planning for and responding to the effects of adverse shocks and stresses is typically what architects and engineers have always thought of as good standard design practices.

Resiliency | Aug 19, 2021

White paper outlines cost-effective flood protection approaches for building owners

A new white paper from Walter P Moore offers an in-depth review of the flood protection process and proven approaches.