In the wake of President Trump’s unilateral decision to withdraw the U.S. from the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, many in the building industry have optimistically pointed to unstoppable market forces pushing the sector towards a post-carbon future.

Immediately after the announcement, the American Institute of Architects and the U.S. Green Building Council issued separate press releases reaffirming their organizations’ commitments to energy efficiency and renewable energy.

Building product manufacturers such as Interface, Johnson Controls, and Kohler joined developers like Skanska, Jonathan Rose Companies, Winkler Development Corporation, Wynkoop Properties, LLC and more than 900 other companies, 100 Mayors, 150 universities, and nine states to sign the massive “We Are Still In” open letter to the international community. This statement reaffirms the commitment of a broad swath of the economy and society to following through with the greenhouse gas reductions and climate resilience strategies that were negotiated as part of the Paris Agreement.

Leaders in the real estate sector see both short- and long-term advantages to taking this stance. In the short term, energy efficiency lowers operating expenses. Over the long term, buildings that are designed to reduce the impact of future heat waves, power outages, high winds, and flooding will likely benefit from lowered insurance premiums.

In response, projects are beginning to use tools such as Health Impact Assessments to design buildings that protect occupants from the health concerns related to climate change that vary from one location to the next—issues like air pollution, heat waves, the drought/flood cycle, and disease-carrying insects.

Given the acknowledged value of climate sensitive design to real estate investments, it is tempting to simply write off the federal government’s participation in climate change efforts, at least for the next 3+ years. However, before we walk down that road, it is useful to pause for a moment to consider what the building sector stands to lose if the federal government stops participating in the movement to build a climate sensitive society.

The Building Industry is Central to the Paris Agreement

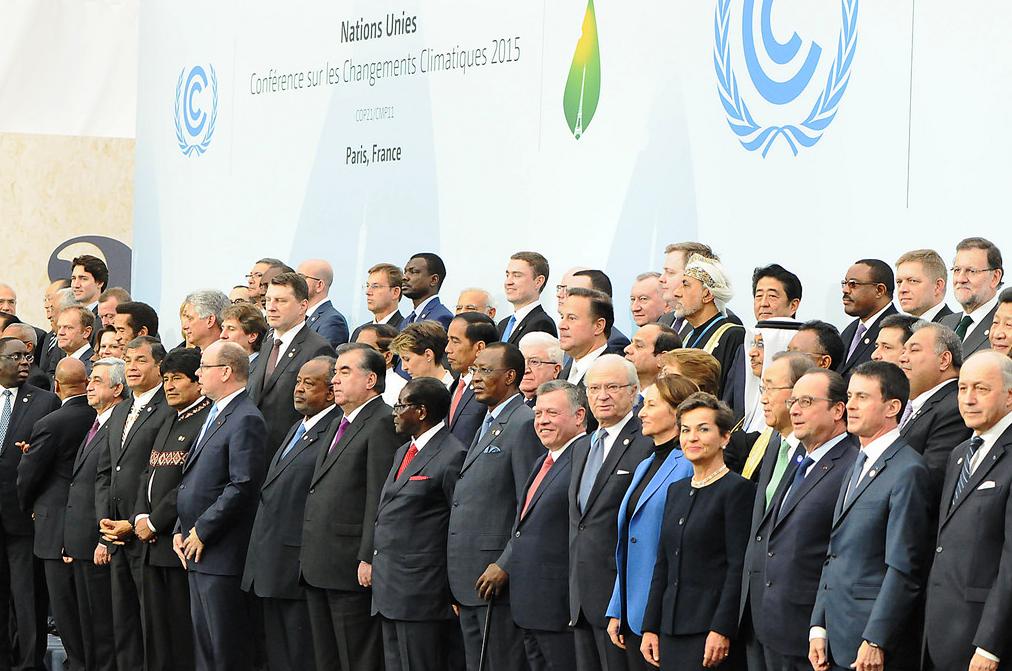

Real estate played a significant role in climate change negotiations, as evidenced by the Global Alliance for Buildings and Construction, which was launched at COP21 in Paris. Its clout stems from the fact that the building sector is simultaneously a major contributor to greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs), the largest source of financial losses when natural disasters strike, and the physical shelter protecting (or, tragically, trapping) individuals during climatic events.

According to the U.S. EPA, it is responsible for more than 30% of U.S. GHGs annually, primarily through the use of electricity and heating oil for building operations. Furthermore, if transportation is included (since the location of buildings relative to each other is a major factor in the type of transportation used to move people and goods from one location to another), what is collectively called the built environment accounts for fully 60% of total U.S. GHGs.

Buildings and infrastructure also make up the majority of losses claimed through the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) after climatic events. And, that amount is growing. The annual average of billion-dollar events from 2012 to 2016, 10.6, is almost twice the long term average of 5.5 from 1980 to 2016.

While it may seem obvious that the purpose of buildings is to shelter their occupants from the elements, it is worth considering the building stock’s current level of performance when the power and water have been cut off. Some of the most tragic news stories from Hurricane Katrina and Superstorm Sandy related the ordeals of patients and residents trapped in buildings after the power and water went out. The cost to society of a building failing to protect its inhabitants during a natural disaster can be significant. For example, a 2011 study estimated that the medical expenses associated with just 6 extreme weather events from the previous decade amounted to $14 billion above and beyond the costs that are typically accounted for in FEMA estimates.

Design decisions also play a role in many of the indirect health effects of climate change. For example, both climate change and the built environment played a role in transmission of the Zika virus in 2016 – climate change by lengthening the number of days that the primary carrier mosquito can transmit the disease; and, the built environment by regulating exposure to Zika-carrying mosquitoes through measures such as air conditioning, window screens, and regularly cleaning or throwing away any outside receptacles that could hold water.

And, the Federal Government is Central to De-carbonizing the Building Industry

If the building industry is aligned with other areas of private industry in a commitment to move away from fossil fuels, then why the furor over the U.S. federal government pulling out of the Paris Agreement?

While it is true that most of the action on climate change is taking place at the state and local level, the federal government plays a pivotal role in coordinating action across the country. For example:

1. While building codes are set at the local level, the federal government sets baseline performance standards for energy efficiency targets, renewable energy generation, flood safety measures, and other elements of land use policy that reduce GHGs and protect building occupants during and after extreme weather events. In order for the real estate sector to meaningfully contribute to the Paris Agreement, carbon neutral building, neighborhoods, and communities must become the norm. By withdrawing the U.S. from the Paris Climate Agreement, the Trump Administration is signaling that federal agencies will no longer coordinate that transition. As a result, real estate developers working in multiple jurisdictions could face a growing disparity in regulations as some regions (such as cities that signed on to the Mayors National Climate Action Agenda) accelerate regulations phasing in carbon neutral requirements in an attempt to offset the lack of progress in other areas of the country.

2. The federal government is the ultimate technology accelerator. It can use financial instruments such as subsidies, grants, and challenges to channel research into solving the large, remaining questions about de-carbonization, such as – How can we decentralize the electrical grid? How will we redevelop urban and suburban areas to reduce car use? How can existing buildings be retrofitted to increase energy efficiency and passive survivability (i.e., continuing to function after the power goes out)? President Trump’s proposed budget ignores questions like these that are looking towards the future, doubling down instead on subsidies to the fossil fuel industries of the past. The result, if accepted by Congress, places the U.S. clean energy and green building industries at a disadvantage compared with other countries.

3. The federal government is often the place where new building technologies are brought to scale for the first time. The General Service Administration (GSA) owns or leases over 375 million square feet across 9,600 buildings. Due to its sheer size, it can sway the marketplace by simply adopting an innovative policy. For example, the GSA’s work testing energy efficiency, water efficiency, indoor air quality, and sustainable materials innovations have influenced the growth of the green building industry since the 1970’s. It is currently working towards achieving carbon neutrality by 2030, a goal that may fade in the current political climate – with corollary repercussions to the entire building industry.

4. Finally, the federal government collects and standardizes most of the data that is used to quantify improvements in energy efficiency, renewable energy, indoor air quality, and the health effects associated with building design. The federal government’s role in spurring the explosion of technologies using big data over the past five years cannot be overstated, including in the real estate industry. There is growing demand among developers, financers, and owners to quantify the benefits of designing net-zero, healthy buildings. Gathering data locally is expensive. And, unless a single set of guidelines are followed, it is impossible to compare one jurisdiction with another. Even if data is collected at the building scale to track performance, chances are that the reference baseline data originated in a federal database. The trend in the Trump administration is against data collection and dissemination. And, without the need to track progress towards Paris Agreement commitments, federal agencies may no longer feel pressure to update key data sets or even share historical records.

Cities, states, and industry should be celebrated for their courage and resolution to continue moving the U.S. along the path to meeting and exceeding the commitments pledged by the Obama Administration.

However, for the reasons outlined above, among others, it is important to continue pushing the Trump Administration to reconsider the decision to withdraw from the Paris Agreement. Perhaps the language of real estate will change President Trump’s mind, as he begins to see the negative repercussions of his decision on his “home” sector of the economy.

About the Author: Adele Houghton, AIA, MPH, LEED AP BD+C, O+M, ND, is President of Biositu, LLC, a strategic consulting company dedicated to leveraging environmental sustainability to enhance community health. She is a licensed Architect in the state of Texas and a LEED Accredited Professional with specialties in Building Design & Construction, Operations & Maintenance, and Neighborhood Development. She received a Master of Public Health and a Certificate in Public Health Informatics from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Related Stories

| May 14, 2013

Paints and coatings: The latest trends in sustainability

When it comes to durability, a 50-year building design ideally should include 50-year coatings. Many building products consume substantial amounts of energy, water, and petrochemicals during manufacture, but they can make up for it in the operations phase. The same should be expected from architectural coatings.

| May 9, 2013

10 high-efficiency plumbing fixtures

From a "no sweat" toilet to a deep-well lavatory, here's a round up of the latest high-efficiency plumbing fixtures.

| May 9, 2013

Post-tornado Greensburg, Kan., leads world in LEED-certified buildings per capita

Six years after a tornado virtually wiped out the town, Greensburg, Kan., is the world's leading community in LEED-certified buildings per capita.

| May 3, 2013

'LEED for all GSA buildings,' says GSA Green Building Advisory Committee

The Green Building Advisory Committee established by the General Services Administration, officially recommended to GSA that the LEED green building certification system be used for all GSA buildings as the best measure of building efficiency.

| Apr 25, 2013

Colorado State University, DLR Group team to study 12 high-performance schools

DLR Group and the Institute for the Built Environment at Colorado State University have collaborated on a research project to evaluate the effect of green school design on occupants and long-term building performance.

| Apr 24, 2013

North Carolina bill would ban green rating systems that put state lumber industry at disadvantage

North Carolina lawmakers have introduced state legislation that would restrict the use of national green building rating programs, including LEED, on public projects.

| Apr 22, 2013

Top 10 green building projects for 2013 [slideshow]

The AIA's Committee on the Environment selected its top ten examples of sustainable architecture and green design solutions that protect and enhance the environment.

| Apr 16, 2013

5 projects that profited from insulated metal panels

From an orchid-shaped visitor center to California’s largest public works project, each of these projects benefited from IMP technology.

| Apr 12, 2013

Nation's first 'food forest' planned in Seattle

Seattle's Beacon Food Forest project is transforming a seven-acre lot in the city’s Beacon Hill neighborhood into a self-sustaining, edible public park.