|

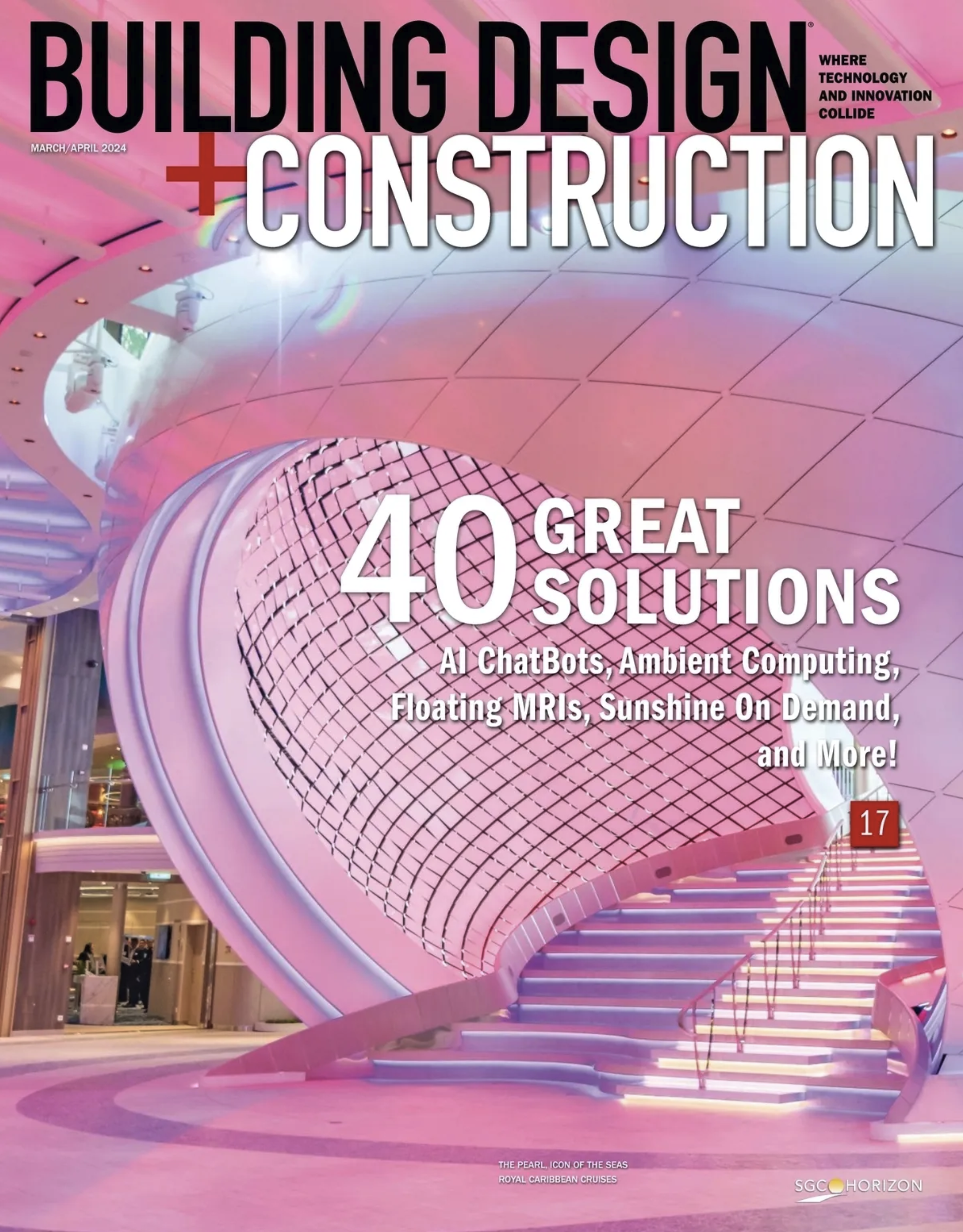

| The solar shade of the Art Institute of Chicago’s Modern Wing was designed to collect and redirect natural light from the north and filter out intense southern light. |

Italian architect Renzo Piano refers to his $294 million, 264,000-sf Modern Wing of the Art Institute of Chicago as a “temple of light.” That's all well and good, but how did Piano and the engineers from London-based Arup create an almost entirely naturally lit interior while still protecting the priceless works of art in the Institute's third-floor galleries from dangerous ultraviolet rays?

Piano addressed that concern by hanging a 216-foot-wide “flying carpet” canopy over the glazed roof of the Modern Wing's east building to filter light and eliminate the threat to the art. This sunshield, supported by steel bracings above the museum's third-floor galleries, is composed of thousands of extruded aluminum “blades” precisely angled to collect and redirect natural light from the north and filter out the dangerous and more intense southern light. Additional screening and computer-adjusted electrical lighting achieve the ideal combination of appropriate lighting, reduced electrical expenses, and art preservation. All of this contributed to the Modern Wing, which opened last May, achieving LEED Silver certification.

“This is made easier in a city that is built on precise north-south and east-west axes, perfectly in tune with the cycle of the sun, like a solar machine,” Piano wrote in notes to his original Modern Wing drawings.

|

| The sprawling sunshade also shields patrons from the sun on the Art Institute’s third-floor, 3,400-sf viewing deck that leads to a bridge to nearby Millennium Park, seen here from the viewing deck. The bridge was also designed by Renzo Piano. |

Robert Lang, lead structural engineer on the project, has been with Arup for 27 years and has spent 20 of those years working with Piano on his projects. He's worked on similar shading and screening devices for Piano's designs of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Lingotto Factory Conversion in Turin, Italy, and the Beyeler Foundation near Basel, Switzerland.

The blades are roughly 13-and-a-half feet long and are situated very crudely at an angle of 45 degrees, says Lang. “They are sculpted and shaped so that they're structurally stable,” he says. “At the low end they're open to the north to allow the indirect northern light in. At the east and west ends they have a series of fins attached to them to catch and block southern light.”

There are more than two thousand small blades on the 46,600-sf “flying carpet,” each supported at two anchor points. The blades were computer-modeled by Arup for maximum energy efficiency and custom fabricated by Sapa RC Profiles in Belgium, which shipped each blade to the site ready for installation. Inside the Modern Wing, a finely calibrated dimming system uses photocells to adjust the supplied lighting to fluctuations in daylighting levels according to time of day, season, and weather. The ceiling and roof of the Modern Wing have two layers of glass and two separate shading systems.

|

| This sketch by architect Renzo Piano shows how building orientation was used to gather and take advantage of northern light at the Art Institute. |

All of Piano's shading devices share common elements from project to project, but the Art Institute's solar shade had to be specially reinforced to withstand changing temperatures and winds of the city's lakefront. “The climate in Chicago, being as severe as it is, was a concern,” says Lang. “For the force of wind, the blades were designed to withstand movement due to high wind by heavy anchoring in the two positions they were affixed to.” Horizontal directional movement was less than 1.1 inches.

“When it comes to temperature fluctuation, we basically allowed the shade structure to expand and contract due to temperature, always away from the center,” says Lang. “The ends of the roof need to be quite large, and the steelwork was anchored to the support polls and outer walls, one solidly, the other less solidly, to allow for expansion and contraction.”

Each of Piano's Modern Wing flying carpet canopies extends its edge panels out past the last supporting side of the building below to increase the sense of lightness, so the solar shade appears to dissolve at its endpoint. Each roof beam supporting the Art Institute's flying carpet was fabricated offsite and sent to the site as a single piece to be installed.

|

| This photo of the ceiling of the East Building, taken during construction, shows the rooftop blades without interior shades below the glass roof. |

Inside each beam is a prestressed steel joint that was joined onsite to the lower structure or another beam. Each beam had to be installed in sequence, as the beams make up a web of tolerances that all depend on one another. The intricate web spun by Piano created the desired look of openness and weightlessness.

“I think the story we are telling with the new addition is about accessibility,” Piano wrote in his notes about the addition. “It's about openness. It's about a building that should not be intimidating.”

Related Stories

| Aug 11, 2010

8 Things You Should Know About Designing a Roof

Roofing industry expert Joseph Schwetz maintains that there is an important difference between what building codes require and what the construction insurance industry—notably mutual insurance firm Factory Mutual—demands—and that this difference can lead to problems in designing a roof.

| Aug 11, 2010

Seven tips for specifying and designing with insulated metal wall panels

Insulated metal panels, or IMPs, have been a popular exterior wall cladding choice for more than 30 years. These sandwich panels are composed of liquid insulating foam, such as polyurethane, injected between two aluminum or steel metal face panels to form a solid, monolithic unit. The result is a lightweight, highly insulated (R-14 to R-30, depending on the thickness of the panel) exterior clad...

| Aug 11, 2010

Nurturing the Community

The best seat in the house at the new Seahawks Stadium in Seattle isn't on the 50-yard line. It's in the southeast corner, at the very top of the upper bowl. "From there you have a corner-to-corner view of the field and an inspiring grasp of the surrounding city," says Kelly Kerns, project leader with architect/engineer Ellerbe Becket, Kansas City, Mo.

| Aug 11, 2010

AIA Course: Historic Masonry — Restoration and Renovation

Historic restoration and preservation efforts are accelerating throughout the U.S., thanks in part to available tax credits, awards programs, and green building trends. While these projects entail many different building components and systems, façade restoration—as the public face of these older structures—is a key focus. Earn 1.0 AIA learning unit by taking this free course from Building Design+Construction.

| Aug 11, 2010

AIA Course: Enclosure strategies for better buildings

Sustainability and energy efficiency depend not only on the overall design but also on the building's enclosure system. Whether it's via better air-infiltration control, thermal insulation, and moisture control, or more advanced strategies such as active façades with automated shading and venting or novel enclosure types such as double walls, Building Teams are delivering more efficient, better performing, and healthier building enclosures.

| Aug 11, 2010

Glass Wall Systems Open Up Closed Spaces

Sectioning off large open spaces without making everything feel closed off was the challenge faced by two very different projects—one an upscale food market in Napa Valley, the other a corporate office in Southern California. Movable glass wall systems proved to be the solution in both projects.

| Aug 11, 2010

World's tallest all-wood residential structure opens in London

At nine stories, the Stadthaus apartment complex in East London is the world’s tallest residential structure constructed entirely in timber and one of the tallest all-wood buildings on the planet. The tower’s structural system consists of cross-laminated timber (CLT) panels pieced together to form load-bearing walls and floors. Even the elevator and stair shafts are constructed of prefabricated CLT.

| Aug 11, 2010

Platinum Award: The Handmade Building

When Milwaukee's City Hall was completed in 1896, it was, at 394 feet in height, the third-tallest structure in the United States. Designed by Henry C. Koch, it was a statement of civic pride and a monument to Milwaukee's German heritage. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 2005.

| Aug 11, 2010

Special Recognition: Kingswood School Bloomfield Hills, Mich.

Kingswood School is perhaps the best example of Eliel Saarinen's work in North America. Designed in 1930 by the Finnish-born architect, the building was inspired by Frank Lloyd Wright's Prairie Style, with wide overhanging hipped roofs, long horizontal bands of windows, decorative leaded glass doors, and asymmetrical massing of elements.