Millennium Partners is in the process of building Winthrop Center, a $1.35 billion mixed-use tower in Boston’s Financial District that, when completed in 2022, will have more than 1.8 million sf of residential, office, and retail space that will pursue LEED Platinum certification. Its 20 floors of office space—which Handel Architects designed in collaboration with MIT’s Metabolic Design Office—are being taken one step further to meet the Passive House Institute’s rigorous standards for energy efficiency.

“We have no hesitation applying Passive House standards to other building types,” says Deborah Moelis, Principal and Passive House designer with Handel Architects.

The firm’s recent work includes The House at Cornell Tech on Roosevelt Island in New York City, a residential tower that, at 270 feet tall and 272,000 sf, is the largest and tallest building in the U.S. to earn Passive House certification. The standard encourages extreme energy efficiency in buildings through passive design measures, such as an airtight envelope, continuous insulation, heat and moisture recovery ventilation, and minimal space conditioning.

The concept of a “passive” structure that requires little energy to provide satisfactory occupant comfort levels has been around since the 1970s. Germany-based Passive House Institute—whose standards were applied to the Winthrop Center and House at Cornell Tech projects—dates back to 1996. Chicago-based Passive House Institute US (PHIUS) can trace its roots back to 2003. It released its PHIUS+ standard in March 2015, and refined that standard three years later to make it even more climate-specific and cost-sensitive.

“The institute realized that it made less sense to try and save that last inch of energy rather than come up with something that could be applied across the country,” explains Michael Knezovich, a spokesman for PHIUS.

Passive House standards have been applied to the construction of hundreds of residential structures in North America. However, the standard is still looking for its way into the commercial, institutional, and multifamily building sectors. “It’s doable, but it’s more of a one-off,” acknowledges Knezovich.

See Also: Timber grows up

What’s holding back Passive House from having a bigger commercial impact are its low energy use targets. “Energy consumption is driven by the building’s process, and reducing the process side is the hardest part,” says James Hartford, AIA, LEED AP BD+C, CPHC, a Partner with River Architects in Cold Spring, N.Y., which started building to Passive House standards in 2012 and has four associates (including himself) who are certified Passive House consultants.

Other AEC firms believe, however, that standards that dictate lower energy use in commercial buildings could become the norm, as cities like Boston, Chicago, New York, and Seattle update their codes to require that buildings meet certain CO2 emission levels or, in some markets, face stiff fines.

“We’re going to have to design for equipment that runs on extremely low power, and design buildings differently,” predicts Moelis.

Tom Bassett-Dilley, who owns an eponymous architectural firm in Oak Park, Ill., built the first Passive House in the Chicago area, in 2012. He notes that PHIUS+ 2018, which takes into account local climates as well as the density and occupancy of the building, might be more amenable to commercial construction. His firm is currently designing a 45-unit apartment building in Oak Park to pass Passive House muster. He uses energy optimization software, known as BEopt, to measure a building’s energy performance.

Bassett-Dilley estimates that building to Passive House standards adds 5-10% to construction cost. But the result “leads to significant savings on energy” over the life of the building. “Any project is a statement on value,” he says.

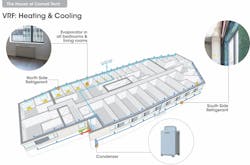

Passive House also “dovetails” with a much bigger industry trend toward electrification to reduce combustion in projects by specifying heat pumps, variable refrigerant flow (VRF) systems, and electric water heaters, observes Julie Janiski, CHPC, LEED AP, Principal of Integrated Design with BuroHappold Engineering, which was on the building team for The House at Cornell Tech.

Subsidies spur construction

Illinois’ Clean Energy Foundation requires that any project seeking grant money must first submit its plans to PHIUS for evaluation. The foundation recently awarded $577,800 to the Park District of Oak Park, Ill., to add 3,000 sf of classroom space built to Passive House standards onto an existing building known as Carroll Center, which is used for preschool-aged classes and after-school programs.

Chris Lindgren, the district’s Superintendent of Parks and Planning, says that originally the older building—which dates back to the 1920s—was going to be torn down. But when the district’s board decided to save it, a board member suggested that geothermal be installed. By tapping the Clean Energy Foundation for grant money, “we were able to do more,” says Lindgren.

This illustration depicts the variable refrigerant flow system design at The House at Cornell Tech in New York City, the largest and tallest building in the U.S. to earn Passive House certification. Image: Handel Architects.

He says it was “a relative snap” to build the addition to Passive House standards. But upgrading the older building required a complete gut, deepening the wall cavities for extra insulation, adding six inches of insulation to the basement floor, and installing triple-pane windows. The addition and reconstruction cost $1.7 million. The Carroll Center’s grand reopening is scheduled for this June.

In Callicoon, N.Y., about 90 miles from New York City, Doug Doetsch, who owns the Orchard at Seminary Hill, is using a $900,000 economic development grant from the state to build a $2 million, two-story, 8,600-sf organic cider mill production facility, the first of its kind to pursue PHIUS certification. The key building components include insulated concrete forms, SIPs panels on heavy timber framing, high-performance windows and doors, with continuous insulation, air barriers, and weather barriers.

Harford of River Architects, the mill’s designer, says that, in essence, this is two Passive House buildings, because of the separate temperature zones for apple storage on the lower floor (50 F to 55 F), and the tasting and event space on the upper floor (68 F).

The mill should be completed next fall. River Architects has other Passive House projects under way, including the conversion of Bethel, N.Y.’s town hall to office space, and the renovation of a school in Brooklyn under the auspices of the New York School Construction Authority.

It’s all in the façade

The most ambitious building to date in the U.S. that is meeting extreme energy efficiency criteria remains The House at Cornell Tech, a 26-story tower housing 352 apartments. BuroHappold states that this project’s primary challenge was reducing the building’s energy consumption by between 60% and 70% in a market whose average seasonal temperatures range from 23 F to 86 F.

Moelis of Handel Architects recalls that none of the building team members had any previous experience building to Passive House standards. The team got much-needed guidance from Lois Arena of Steven Winter Associates, the project’s sustainability consultant, and Luke Falk, a Vice President with the Related Companies’ Hudson Yards Technology.

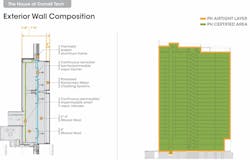

The House at Cornell Tech is one of the most ambitious buildings to be constructed to meet extreme energy efficiency standards. It achieved that with, among other things, an airtight envelope whose façade includes 11 inches of insulation, six inches of which is in the stud cavity. Image: Handel Architects.

Designing to Passive House standards hinges on the façade engineering. Eastern Exterior Wall Systems fabricated the metal panelized wall units for The House at Cornell Tech with 11 inches of insulation, six inches of which was in the stud cavity; thermal breaks in the wall so heat and cold didn’t seep into the building; and an airtight envelope, says Kenneth Loush, Eastern’s Chief Engineer.

Schuco-brand windows were shop-installed into the panels, accounting for only 23% of the façade’s surface area, says Janiski of BuroHappold. While that worked fine for The House at Cornell Tech because its rooms are small, Janiski acknowledges that keeping the window-to-wall ratio low is a tough sell to developers that are “attracted to glass.” But it’s imperative, she adds, to avoid paying a premium to get triple-pane glass to perform as expected.

The House at Cornell Tech has been a springboard for BuroHappold to consider building other projects to Passive House standards. “It makes you go back to basics,” says Janiski.

Editor's Note: Additional information about PHIUS and Passive House Institute in Germany were included after this article was initially posted.