Tall schools, tight spaces: Giving students access to the outdoors requires considerable creativity

This fall, GEMS World Academy Middle-Upper School is scheduled to open in Chicago. This 13-story, 213,000-sf school for grades 6-12 would be among the latest—and tallest—of the multilevel urban elementary and secondary schools that have been springing up around the country.

Vertical schools “are becoming more commonplace, even outside of urban areas,” says Sean O’Donnell, AIA, Principal with Perkins Eastman’s Washington, D.C., office, whom BD+C interviewed with Christine Schlendorf, AIA, LEED AP, a Principal in the firm’s New York office.

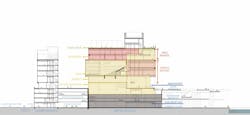

One of Perkins Eastman’s newer school projects, which it designed in collaboration with Wilson Butler Architects, is the $124.5 million, 153,500-sf Boston Arts Academy. Upon completion in 2021, it will replace a 121,000-sf school that was a 1998 adaptive reuse of a 1920s-era post office warehouse. The new five-story academy is located across the street from Fenway Park on less than one acre of land.

O’Donnell says that vertical schools are a realization by school districts and developers that the acreage needed for one- or two-story urban schools built horizontally either isn’t available or is too expensive to justify academic construction, which must compete for land with booming office and healthcare sectors and tax-generating districts for innovation, science, and entertainment.

“Multilevel schools are a balancing act” that weighs the cost of land against the growing demand from families moving back into cities, says Todd Ferking, AIA, Principal with DLR Group in Seattle. His firm recently made proposals to that city’s officials for a new downtown elementary and high school.

Verticality has some plusses, according to AEC firms that have engaged such projects recently. One big advantage seems to be security, as taller buildings generally have fewer access points.

Getting sufficient natural light into taller urban schools is not the challenge one might expect, either. O’Donnell notes that because the Boston Arts Academy will be comprised of so many big, boxy interior spaces, getting light deeper into each floor won’t be a problem.

The GEMS Middle-Upper School is set back from the street 25 feet, and is situated so that its main walls are perpendicular, and the north side faces East Wacker Driver on an angle, resutling in a courtyard that enables natural light to enter the school's Design Labs, one floor down from the street, says Lynne Sorkin, AIA, Director and Education Practice Leader for bKL Architecture, which designed this building as well as the adjacent 10-story GEMS World Academy Lower School.

The five-story Clark Avenue School in Chelsea—a 5th to 8th grade drama-focused feeder for Chelsea High School that opened last fall—has stairs that are “light-filled, wide, with colors, and welcoming,” says Lori Cowles, a Principal with HMFH Architects, the school’s designer.

Stairs play an important role in taller school’s circulation strategies. Perkins Eastman’s Schlendorf spoke about the 10-story Avenues, a pre-K-12 school in New York City, whose judicious use of “convenience stairs” helps connect students on various floors, says Schlendorf.

Providing that kind of transparency for students is now a central feature of taller school design. Another of HMFH’s projects is the six-story Arlington (Mass.) High School, whose design called for large open interior spaces that allow students to see more of what’s going on above and below them. “This ties the levels together,” says Cowles.

But as schools get taller, their programming can get more complicated, according to K-12 school experts.

DLR Group has been working on the 278,893-sf Huili School for the Wellington International Education Group in Shanghai, China. The nine-story first phase, for grades 1 through 9, opened last September, and Ferking says verticality divides the building into two distinct sections, with an open lecture area and lab space on the sixth floor. (Phase two, for grades 10-12, which is scheduled to open in 2021, will be two or three stories.)

The Huili School—which eventually will be surrounded by mixed-use high-rises—includes an indoor track, swimming pools, and an indoor practice soccer field.

Ferking says that student and faculty egress is always a concern in taller schools. That’s why, at Huili, classrooms for older (and presumably more mobile) kids are on higher floors. To provide easier movement for its youngest students between the Lower and Upper Schools, GEMS’ larger communal and assembly areas, like its gym and 500-seat auditorium, are located on lower floors, says bKL’s Sorkin.GEMS Middle-Upper School also has six elevators.

To assuage safety concerns about picking up and dropping off students, the school has an arrangement with a nearby parking garage, says Isaac Persley, who is managing the GEMS project for bKL “Careful placement of entrances and strategies to minimize traffic can limit neighborhood disruptions, while enabling supervision of students,” says Sorkin.

Finding fresh air

Perhaps the greatest potential drawback of taller urban schools is the lack of access they provide their students to outdoors. These schools are usually on tight lots with little, if any, play areas or fields. So they have to make do with the outdoor space that’s available to them, or make arrangements with other public facilities.

The recently completed renovation and expansion of the K-12 Children’s School of Atlanta, a Perkins+Will-designed, three-story building that sits on 2.7 acres within the city’s midtown, uses the sports fields at nearby Piedmont Park, which acts essentially as a virtual extension of the school’s outdoor learning activities.

On the top floor of GEMS Middle-Upper School is an 8,000-sf artificial-turf recreation area that serves as a location for outdoor classes (weather permitting), a place for independent study, a meeting spot for school clubs and other organizations, and a place for students to unwind between classes. There’s a patio on the north side of the building’s roof deck. And the classrooms have access to courtyards on different floors.

Before construction began on the 115,235-sf Clark Avenue School in Boston, “there wasn’t a tree on the site,” recalls Cowles. The older existing school it would replace was surrounded by blacktop, and there was nowhere for students to hang out after classes. HMFH’s design for the new school introduced open space that includes a garden, and an outdoor performance space with tiered bleachers. This outdoor space, says Cowles, takes up about one-third of the school site’s 1.2 acres.

This school was built in two phases: The first, five-floor building (that was only nine feet from the old school that stayed open during construction) includes classrooms, the cafeteria, and kitchen. The second phase, with fewer floors, houses the gym, band classrooms, and other specialty spaces.

One side of Clark Avenue School abuts its neighborhood. AEC firms say that school districts are paying closer attention to establishing and maintaining relationships between their schools and surrounding communities. Boston Arts Academy—which will include a wellness center and 500-seat theater—is being positioned as a “beacon” for its neighborhood.

A few years ago, the three-story, 80,000-sf McCarver Elementary School reopened in a high-poverty area in Tacoma, Wash. DLR Group’s design for this gut renovation project (Skanska was the contractor) created space that would become a “hub” and “collection point” for the community, says Ferking. As part of its renovation, the school got new playground equipment and a synthetic sports field.