It has long been apparent that colleges and universities are engaged in an arms race to attract top student-athletes, with ammunition that includes extravagant training centers and stadiums.

John Roberson is on the front lines of those battles. As CEO of Advent, a Nashville, Tenn.-based branding consultant that has worked with a wide range of AEC firms, he sees many colleges whose recruiting strategies are based on having the largest, most state-of-the-art athletic facilities.

However, he observes wryly that these facilities can be “obsolete” as soon as they open, because another university always has something gaudier on deck.

What’s often missing from schools’ recruitment efforts is “an overlay of narratives” that informs the student-athlete how he or she will fit into the place. “It’s about the immersive messaging that’s wrapped around the product,” says Roberson.

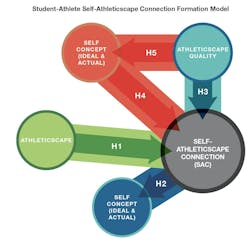

To help bring a more complete picture into focus for student-athletes, colleges are stepping forward with “athleticscapes” that express the totality of the manmade environment and physical surroundings of the school’s athletic department. The goal, says Roberson, is to shape the student-athlete’s perceptions of the quality of the institution.

In planning its new Athletes Village complex, the University of Minnesota wanted the spaces to convey a number of messages to prospects: that Minnesota has a hardworking class of people; that the University of Minnesota is the only Division 1 school in the state; and that Minnesota’s lifestyle, as depicted in the facility’s design, is rich and varied.

“When college officials talk about buildings, it’s about the emotion the building embodies,” he says. “That’s not something that colleges want to leave to chance.”

Roberson points out, though, that reconnaissance is “very thin” on what criteria high school athletes—so-called “Centennials,” or Generation Z—use to gauge colleges’ athletic programs. To fill that void, Advent has prepared its latest Student-Athlete College Choice Study, which it conducted with the Brock School of Business at Samford University.

The study, based on focus groups and an online poll of 783 college students, found that facility design elements significantly increase student-athletes’ perceptions on 12 of 32 choice determinants. However, a more surprising finding revealed that five of the top seven factors that determine where student-athletes enroll relate directly to how a school will help that student achieve his or her post-athletic career objectives.

As 30% of NCAA Division 1 student-athletes intend to major in business, the study suggested that colleges’ athletic departments should partner with their business schools in their recruitment efforts.

The study noted that student-athletes’ impressions of a school can be affected by little things, such as the tidiness of a coach’s desk (which, in their minds, might reflect the coach’s organizational skills), or the comfort of an interview room.

The school hired a branding consultant (Advent) to work with the project's design architect BWBR and general contractor Mortenson Construction.

Roberson is a big proponent of incorporating social media into a college’s branding because students these days are “message driven.” An athleticscape, synchronized properly, will reinforce the recruit’s perception of his or her brand in ways that assert individuality.

“In the same way people engage in consumption behavior to construct their personal identity, we believe that mental associations student-athletes form about the athletic department are critical to the development of their own self-concepts,” the study stated.

It takes a Village to prepare student-athletes for life

A prime example of an athleticscape in action is the University of Minnesota’s Athletes Village, a $166 million, 338,000-sf, three-building complex that opened last January on seven acres of the school’s East Bank campus in Minneapolis.

This project dates back to 2012, when the university retained Populous to conduct a needs assessment of the school’s athletic program. The study concluded that the program needed a “village” to consolidate and broaden its physical assets.

Scott Ellison, the university’s Associate Athletic Director, and Jeff Keiser, Assistant Athletics Director for Creative and Branding, recall that the university hired Advent as a branding consultant on this project, working with design architect BWBR and general contractor Mortenson Construction. Advent spent several days “story mining,” interviewing nearly 40 people to “explore what students hold dear,” explains Robertson.

The Athletes Village has greatly expanded its space for training and learning. Its Leadership Center (above) offers spaces and programming where student-athletics can hone skills to prepare them for life outside of sports.

Keiser says the university wanted Athletes Village to convey a number of messages to prospects: that Minnesota has “a super-hardworking class of people”; that the University of Minnesota is the only Division 1 school in the state; and that Minnesota’s lifestyle, as depicted in the facility’s design, is rich and varied.

The messaging starts at the Athletes Village’s entrance, where 12 projection screens with a total of 23 million pixels flash a continuous loop of the school’s athletic highlights. That messaging can be changed within minutes.

The Village’s other features include:

• The Lindahl Academic Center, with 34 study rooms (up from eight in the school’s old facility), and a staff that helps athletes choose courses. The Academic Center offers post-grad job placement services.

• The Land ’O Lakes Center for Excellence (for which the butter maker paid $18 million for naming rights). This includes an interactive tabletop where students, parents, and friends can find and link up with alumni in the professional world. A 325-seat nutrition center is open to all students for breakfast and lunch; it is reserved for athletes for dinner. The nutrition center’s test kitchen offers cooking classes.

• A locker and training area whose north wall is almost entirely made of electrochromic glass.

• Separate practice basketball courts for the men’s and women’s teams.

• A Leadership Center, where student-athletics can hone skills to prepare them for life outside of sports.

• A 16,000-sf weight room that’s 10,000 sf larger than its older counterpart and can accommodate 160 athletes at once.

• An indoor football practice field that’s 200 feet wide and 85 feet high.

• A $13 million track and field facility is scheduled to open this fall.

The university’s head football coach, P.J. Fleck, has referred to the Village as “a life complex.”

The Locker/Training level (below) houses several hot/cold plunge tubs, underwater treadmills for injury recovery, a football-shaped locker room, and a skyway to the indoor practice facility. The Academic Center (not shown) has 34 study rooms, more than four times the number in the school’s older facility. Its 16,000-sf weight room is 60% larger. And its nutrition center seats 325 and is open to all students for breakfast and lunch. The university’s head football coach, P.J. Fleck, has referred to the Village as “a life complex.”

athleticscapes form impressions at the high school level, too

Athleticscapes aren’t confined to colleges or universities. The concept has been creeping into select high schools.

In February, Phillips Academy Andover in Massachusetts dedicated its new 98,000-sf athletic and academic center. Along with courts for tennis, squash, and basketball, the rooms in this building were designed for multipurpose use, says Stephen Sefton, Associate Principal in the Boston office of Perkins+Will, the project’s design architect.

The building’s upper level includes space that looks onto the football field and can be used for dance and yoga classes, dinners and school galas, and office functions, and as a spectators’ balcony.

P+W did the facility assessment and athletic master plan that incorporated existing structures like the hockey rink and outdoor track.

“We created a short- and long-term vision for the school,” says Sefton. He notes that one of the first things his firm does on projects like these is to clearly identify the school’s brand and how the building manifests it. In Phillips Academy’s case, “an important element of its branding is an emphasis on inclusion.”

Sefton believes that every school, at all levels, needs to consider and recognize competition from the standpoint of the student, the alumni, and the fan.

For its study on student-athlete choices, Advent devised this diagram to simplify its thesis that student-athletes show a stronger connection with a school’s “athleticscape” when that environment comes closest to reflect the students’ preconceptions of the place.