Small-venue theaters play starring cultural and economic roles in New York City’s economy

By John Caulfield, Senior Editor

There are 748 small theater organizations in New York City that generated $1.3 billion in economic output and supported 8,400 jobs that paid $512 million in annual wages in 2017.

Those statistics come from a 60-page economic impact study that the New York Mayor’s Office of Media and Entertainment (MOME) recently completed with consultative assistance from BuroHappold Cities, the engineering firm’s team that provides strategic planning, project management, and analytical services; and 3x3 Design, which provides social innovation and design strategies for urban and economic development initiatives.

The release of this study coincides with the city’s first-ever public awareness campaign in October that encouraged New York’s residents and visitors to support the city’s small theater scene in all five of its boroughs.

The city commissioned this study at a time when people working in the theater industry continue to face unstable compensation and rents that, over the period analyzed, rose more than double the industry’s wage increases, on a percentage basis. “Housing affordability and rising living costs have particularly outsized implications for this labor force,” the study states.

New York has long been the epicenter for live theater in the United States, and a launching pad for some of the country’s most famous actors. Throughout the city, there are 226 small-venue stages with an aggregate of 51,779 seats. Its 600 production companies include 97 that produce and present theater (with physical locations), and 51 theater organizations that exist under umbrellas of large, non-academic institutions.

The small-theater sector's economic output increased by 5% annually between 2014 and 2017, a faster clip than the city's overall economic output. Images: New York Office of Media and Entertainment

Over the past decade through 2017, over 280 theater organizations have been founded in New York City, compared with the more than 100 that either closed or relocated.

Between 2014 and 2017, the economic output of the small theater industry increased a 5% annually, a percentage point higher than the total citywide economic output. Consequently, the study calculates, the small venue theater industry’s growth has outpaced baseline economic growth by 20% for economic output, and by 100% for job and wage growth.

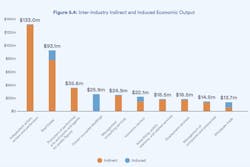

The so-called “induced” economic impact—from employees working directly or indirectly for the small theater industry who spent their wages in New York City—found that these workers generated $208 million in output and created nearly 2,000 more jobs in 2017.

Indirect and induced economic output from people employed in the small theater arena outpaces that from other sectors.

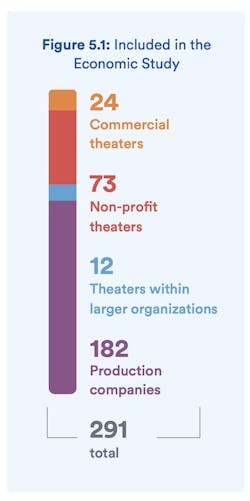

The report includes 267 nonprofits (73 theaters, 182 production companies, and a dozen theaters within larger organizations). The larger organizations (i.e., those with revenue greater than $5 million) account for only 3% of the total number of theatres but generate 74% of the small theater industry’s revenue. Conversely smaller organizations (with under $500,000 in revenue) make up nearly two-thirds of the sector but contribute only 26% of the industry’s revenue.

For large and small nonprofits, programming services—ticketing, space rental, etc.—accounted for 41% of their total annual revenue, on average, with that same percentage coming from private contributions and grants, and 10% from sources such as merchandising and concessions. Government kicks in 8% of the nonprofits’ revenue.

Commercial organizations, on the other hand, may account for only 3% of New York’s small-venue theater organizations, but their 21 theaters generate 11% of the industry’s total revenue. Four commercial theaters alone generated $48.8 million of the $63 million in 2017 revenue that all commercial theaters produced.

Nonprofits account for the lion's share of small theater organizations.

The future growth within the small theater sector will depend on a number of factors, not the least of which being space availability. The study points out that access to long-term space has given theater organizations the curating flexibility of presenting work that’s produced by outside companies.

Nomadic theater production companies must navigate their space needs on a project-by-project basis. That’s not necessarily a negative, says the study. “[L]ack of site-specific obligations can act as an advantage, allowing [the companies] to be more flexible and adaptive as an organization and to tailor space acquisition to the needs of each specific production.”

In addition, interdisciplinary collaboration and production in spaces beyond traditional theater venues are common in New York’s small theater arena. “This component of the sector has been expanding since the 1980s with the increased development of multimedia and video work,” says the study.

Another factor for sustaining growth of this sector will be the funding support it receives from private and public donors. Newer and less-established theaters typically have more difficulty tapping foundation funding.

Smaller theaters also rely on the city for support. In fiscal 2019, The New York City Department of Cultural Affairs (DCLA) alone provided $45.6 million in expense and operating support for 383 organizations working in theater and/or multidisciplinary arts. (That amount equaled nearly 23% of the department’s expense budget.)

A breakdown of the theater organization types included in the economic impact study.

Since 2000, DCLA has provided funding for 50 theater-related construction projects throughout the city. More than half of the projects received funding in the $10 million range. In addition, the New York State Council on the Arts has contributed to capital improvements of New York City theaters and institutions.

Corporate donors have been relatively few in this sector, and they tend to channel their funding to middle- to larger-tier organizations.

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing small theater organizations is audience retention and expansion. Small theaters are competing for consumer dollars against all kinds of entertainment options (including multimillion dollar shows on Broadway). The diminution of print media makes it harder for small theaters to make their productions known to the public, even given the fact that small-theater productions are more likely to attract local residents than tourists.

To address the audience quandary, theaters are using innovative marketing, including social media and other online platforms to target younger people. The theaters are initiating strategic partnerships with other theaters for co-productions, or even with neighborhoods to promote shows. And they are attempting to cultivate audience segments—such as people of color or those with disabilities—that historically have been under-represented in the theater.

“Theaters are looking to be more rooted in a specific place, deeply embedded in the local framework and engaged with local communities,” the study states.

That study posits that small-venue theater is an integral part of the city’s artistic character, and makes several recommendations about what the city could be doing to help this sector grow.

These include:

•Targeting its support at boroughs outside of Manhattan to help facilitate partnerships with grassroots organizations.

•Supporting promotional and awareness campaigns that spotlight small venue theaters to cultivate audiences.

•Convening sessions to introduce potential partners and mentors who might have new ideas about mining critical resources for these theaters.

•Coordinating different city agencies like DCLA and MOME to support issues surrounding theater owners and operators.

•Building on the theater sector’s existing workforce training partnerships that provide pipelines for employment and union membership, and find ways to support smaller theater companies with their labor needs.