A new study wonders how many retiring adults will be able to afford housing

By John Caulfield, Senior Editor

In 1998, households with owners or renters 65 or older accounted for nearly 20% of 102.5 million total households. Twenty years later, older households had increased by more than half, and accounted for just under 26% of the total 127.6 million, according to Census Bureau.

As the number of older households has risen above 33 million and continues to climb, America has been grappling with a severe shortage of affordable housing options. A consequence of this debacle, according to a study released today by the Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University, is that that housing cost burdens for this older age group have reached “an all-time high.”

And the future looks precarious for households led by adults 50 to 64 years old, nearly 10 million of which—roughly 18% of the households in that group—are cost burdened, “ensuring financial and housing security in retirement will be a struggle,” the Joint Center cautions.

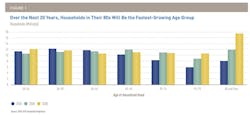

As in its other reports on housing, the Joint Center surveys recent statistics to hypothesize about likely future outcomes. It estimates that U.S. households age 65 or older will reach 34% of the total by 2038. Driving that growth will be households aged 75-79, which are expected to increase by 49% through 2028, and by another 20% in the following 10 years. By 2038, households age 80 or older could account for 12% of the total.

A sizable percentage of adults are entering retirement financially struggling to afford decent housing. Chart: Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University

The Joint Center foresees a diverse older household mix that is more Hispanic. The share of older white households will reduce to 70% of the total by 2038, from around 78% today.

Older households will also be smaller. For example, 57% of households age 80 or older consist of a single resident. That’s an issue, explains the Joint Center, because older individuals living alone tend to have higher disability rates and lower incomes than same-age couples.

(The report finds that, despite the rise in coliving options, relatively few older adults live with roommates or in group quarters. Minorities, however, are more likely to live in multigenerational households, and that trend should increase.)

Eighty percent of older households were single-family homes in 2017, and most of those buildings were four decades or older, which means they require levels of maintenance and renovation that may beyond the financial means of their owners.

While single-family rental stock has increased in recent years, most of the seven million older renters live in multifamily housing. The Joint Center posits that people in their 80s may prefer multifamily buildings with 50 or more units because they offer accessibility features, like elevators or single-floor living.

Nearly one-third of older households were located in low-population-density communities in 2017, “and their numbers have been rising rapidly,” says the Joint Center. (Between 2000 and 2017 the number of older households located in the least-dense third of a city jumped by 61%.) While older renters are somewhat mobile in terms of their living choices, this age group in general has the lowest household mobility of any age cohort tracked. The Joint Center, however, suggests that the mobility rates of older households might increase as their numbers expand.

Mobility can be a function of available income. And since 2000, retirement-age households have enjoyed much stronger income growth than households in their preretirement years. Not surprisingly, most of those gains went to the highest-income households in this age group. That trend certainly explains why 27% of adults 65-74 were still working in 2018, as well as 9% of those 75 or older.

The Joint Center identifies a widening income disparity separating older households that’s partly reflected in homeownership rates. “These inequalities are important because homeownership provides older households greater housing security and more predictable housing costs than renting,” states the report. In 2016, the median owner age 65 and over had home equity of $143,500 and net wealth of $319,200. By comparison, the net wealth of the same-age renter was just $6,700. Among the 50- to 64-year-old age group, this disparity between the net wealth of owners ($292,000, including $115,000 in home equity) and renters ($5,000) is also substantial.

Click onto an Interactive Map showing where older households are more or less cost burdened.

A growing number of older households carry housing and other types of debt well into their retirement years. Where less than one quarter of homeowners aged 65 to 74 had an outstanding mortgage or home equity loans three decades ago, that number rose to 46% by 2016. Thirty-five percent of this same age group carried credit card balances in 2016, versus 24% in 2001, and their outstanding debt over that period doubled per person. Consumer debt is even more pronounced among the 50-64 age group.

These factors all contribute to the increase in the number of older households paying more than 30% of their incomes for housing, from 2016 to 2017, by 200,000 to nearly 10 million. Half of these older households allocated over 50% of their incomes to housing. Another 10 million in the 50-to-64 age group were cost-burdened, too.

This situation is far more acute among older renters, 54% of whom are cost burdened. But having a mortgage increases the likelihood of being cost burdened: 43% of owners age 65 and over with mortgages had housing-related cost burdens in 2017, compared with 16% of owners without mortgage debt.

The likelihood of being cost burdened increases with age. Among households age 80 and over, 56% of owners with mortgages were burdened in 2017, along with 59% of renters.

Older adults with housing cost burdens may cut back on other budget items, including those essential to health and well-being, especially as healthcare expenses continue to rise, and the cost of food has inflated.

Adults in their 80s will account for a larger portion of America's population over the next two decades. Chart: Joint Center for Housing Studies at Harvard University

A tragic manifestation of these dynamics has been an increase in the number of homeless older adults, up 69% over the past decade, to nearly 7,600, among people 62 or older. More alarming is the estimate that individuals age 50 or older accounted for one-third of the country’s homeless population in 2017, from 22.9% in 2007.

What bodes for younger baby boomers remains to be seen. But the Joint Center cites a recent University of Pennsylvania study that estimated, in New York City alone, the homeless population age 65 or older could increase to 6,900 in 2030, from 2,600 in 2017.

The Joint Center report projects that the population of very-low-income older adult households will grow from 5.3 million in 2018 to 7.9 million in 2038. Demand for subsidized housing could exacerbate over the next two decades as a result of shortfalls in government rental assistance programs.

The Joint Center believes that federal support will be essential to “bridge the gap between the cost of building and operating affordable housing and the rents that low-income older adults can pay.” It also calls for affordable housing that connects residents to support services such as shared meals, recreation, transportation and healthcare coordination.

On a positive note, many states encourage aging in place by covering the cost of certain home modifications for low-income households under Medicaid Home and Community-based service waivers. The Joint Center also notes that 403 communities, along with Colorado, Florida, Massachusetts, New York, and the US Virgin Islands, have joined AARP’s network of age-friendly places that are committed to improving livability for older adults.

More such efforts will be needed, as the U.S. population continues to age, and the economics of aging become less certain. Within the next decade, 18 million Americans will be in their 80s, many living alone on fixed incomes. “The need for affordable, accessible housing and in-home supportive services is therefore set to soar,” the Joint Center asserts. Even for people aging in their current homes, “new transportation alternatives and opportunities for engagement in the community will be critical to their continued ability to live independently.”

Click onto an Interactive Chart showing income levels for two older age groups.

What concerns the Joint Center most is that too many older adults aren’t positioned financially to afford decent housing. And, it decries, “the circumstances of today’s 50- to 64-year-old households suggest that these disparities will persist.”

The Joint Center concludes that the private and public sectors must work together urgently to provide housing and neighborhoods needed by an aging population. “The time for more comprehensive, innovative policies—in the design, financing, construction, and regulation of housing, in urban planning and design, and in the provision of community services—is now. The quality of life and wellbeing of a third of U.S. households depend on it,” the report states.