|

|

Milwaukee City Hall, built in 1896, recently underwent a meticulous reconstruction and renovation that lasted more than four years. |

When Milwaukee's City Hall was completed in 1896, it was, at 394 feet in height, the third-tallest structure in the United States. Designed by Henry C. Koch, it was a statement of civic pride and a monument to Milwaukee's German heritage. It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 2005.

The massive bell tower of City Hall is supported by an armature of vertical and sloping steel trusses and beams embedded within four ornamental masonry and terra cotta gable facades. The design motif is echoed by 20 smaller gables on the east and west facades and larger cross gables at the center and north end of the building. The focus of each gable in the south tower is a white-faced, illuminated clock, just as in the main tower. Coal-fired boilers provided steam heat for the building and drive for the turbines of four DC power generators.

Over the building's century-plus life, the repetitive freeze-thaw cycles of the upper Midwest, combined with the absence of cavity walls for proper drainage, permitted water to damage the building's entire structure and skin. Over time, water from rain, sleet, hail, snow, condensation, and absorption had all but destroyed the integrity of the building's terra cotta and brick envelope, and its steel frame was slowly corroding within its perpetually damp masonry walls.

|

|

A full building assessment of the exterior condition of Milwaukee City Hall was done before construction began. |

In 2001, the Milwaukee Common Council approved funding for a forensic investigation of the building's envelope. The New York office of Simpson Gumpertz & Heger and Wiss Janney Elstner Associates, Northbrook, Ill., sent engineering teams to assess the building's façade from top to bottom.

Both teams brought grim news. The landmark was in need of immediate and extensive repairs and restoration. Experts were brought in to discuss its restoration, particularly for the primary building materials: brick, terra cotta, stone, copper, and slate. Over a three-day period, the recommendations, protocols, and restoration techniques were compiled in a condition assessment report by WJE and evaluated by a group of experts. The consensus: “Do it right and do it now.”

A multidisciplinary team led by architect Engberg Anderson (restoration design, detailing, and project management), SGH (structural studies, forensic investigations, and design), Bloom Companies (structural engineer) and associate architect Quinn Evans | Architects (historic structures report) was selected, with the WJE report as the underlying document to determine standards and procedures.

Because Milwaukee City Hall was built at a time when “master builders” determined the selection and specification of building materials and systems, the Building Team had to work backwards to understand the cause and effect of building detail failures and to redesign precise details, using modern technology that would allow visual repetition of the original. Original materials that still had visual and physical integrity remained in place.

The best available original drawings were scanned and converted to CAD, enabling the team to replicate the original hand-drawn details of the building's sections and elevations. The plan to redetail the historic building using new methods and materials remained consistent throughout the peer review and construction process.

After general contractor J.P. Cullen & Sons, Janesville, Wis., was selected in 2004, the full Building Team—including major subcontractors— had the first of many meetings to set project goals for the restoration—a process that would continue for more than three years. Coincidentally, during that first meeting a big chunk of terra cotta fell from the south tower onto the copper roof, slid off, and crashed onto the street 200 feet below. The incident underscored the urgency of their task and drew the team together from that day forward.

Forensic, design, construction, and scaffolding engineering included installing temporary steel outrigger beams to the south tower to support the upper scaffolding. This was done to allow a reduction in setback that was required to successfully bring scaffolding closer to the upper reaches of the tower.

More than 19,000 pieces of slate and 115,000 pounds of copper were used. Nineteen hundred windows were restored, and precisely 13,404 pieces of terra cotta were replaced. Two hundred thousand pressed bricks were manufactured using techniques akin to those from which the original bricks were made. Tons of additional structural steel members were used to repair and stabilize the clock tower structure.

Eugene Matthews, a decorative terra cotta manufacturer from Northern California, and brick-making expert IXL Brick from Medicine Hat, Alb., were brought in to replicate these materials in the towers and walls. J.P. Cullen & Sons oversaw the painstaking installation of these materials.

In the end, the restoration more than complied with the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties.

“It's a staggering work of preservation and historical accuracy,” said K. Nam Shiu, PE, SE, vice president at Walker Restoration Consultants and a Reconstruction Awards judge. “It's a handmade building, and it's so very difficult to be that true to the original design intent, down to every building material used.”

Related Stories

| May 20, 2014

Using fire-rated glass in exterior applications

Fire-rated glazing and framing assemblies are just as beneficial on building exteriors as they are on the inside. But knowing how to select the correct fire-rated glass for exterior applications can be confusing. SPONSORED CONTENT

| May 13, 2014

19 industry groups team to promote resilient planning and building materials

The industry associations, with more than 700,000 members generating almost $1 trillion in GDP, have issued a joint statement on resilience, pushing design and building solutions for disaster mitigation.

Sponsored | | May 3, 2014

Fire-rated glass floor system captures light in science and engineering infill

In implementing Northwestern University’s Engineering Life Sciences infill design, Flad Architects faced the challenge of ensuring adequate, balanced light given the adjacent, existing building wings. To allow for light penetration from the fifth floor to the ground floor, the design team desired a large, central atrium. One potential setback with drawing light through the atrium was meeting fire and life safety codes.

| Apr 25, 2014

Recent NFPA 80 updates clarify fire rated applications

Code confusion has led to misapplications of fire rated glass and framing, which can have dangerous and/or expensive results. Two recent NFPA 80 revisions help clarify the confusion. SPONSORED CONTENT

| Apr 8, 2014

Fire resistive curtain wall helps The Kensington meet property line requirements

The majority of fire rated glazing applications occur inside a building to allow occupants to exit the building safely or provide an area of refuge during a fire. But what happens when the threat of fire comes from the outside? This was the case for The Kensington, a mixed-use residential building in Boston.

| Apr 2, 2014

8 tips for avoiding thermal bridges in window applications

Aligning thermal breaks and applying air barriers are among the top design and installation tricks recommended by building enclosure experts.

Sponsored | | Mar 30, 2014

Ontario Leisure Centre stays ahead of the curve with channel glass

The new Bradford West Gwillimbury Leisure Centre features a 1,400-sf serpentine channel glass wall that delivers dramatic visual appeal for its residents.

| Mar 20, 2014

Common EIFS failures, and how to prevent them

Poor workmanship, impact damage, building movement, and incompatible or unsound substrate are among the major culprits of EIFS problems.

| Mar 12, 2014

14 new ideas for doors and door hardware

From a high-tech classroom lockdown system to an impact-resistant wide-stile door line, BD+C editors present a collection of door and door hardware innovations.

| Mar 7, 2014

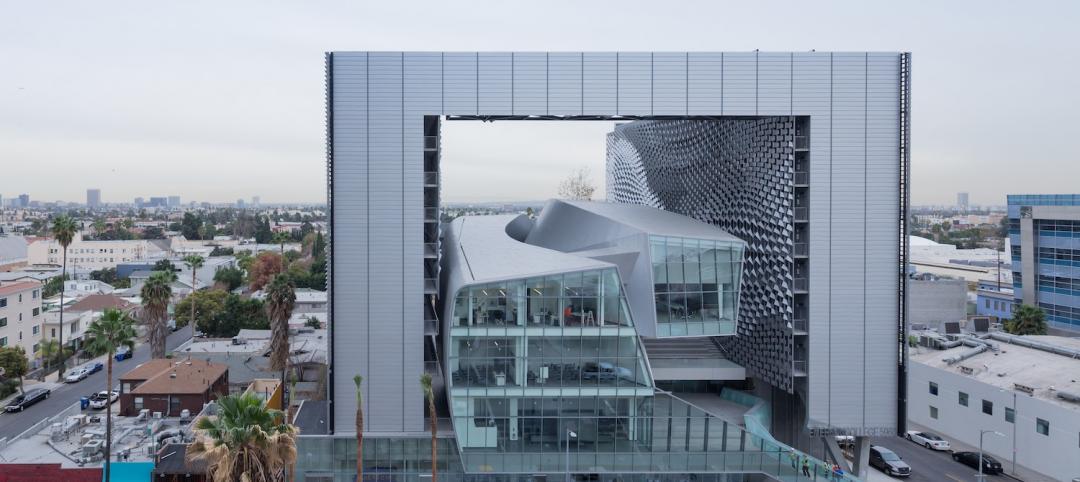

Thom Mayne's high-tech Emerson College LA campus opens in Hollywood [slideshow]

The $85 million, 10-story vertical campus takes the shape of a massive, shimmering aircraft hangar, housing a sculptural, glass-and-aluminum base building.